Inverted House

F ‘21

In collaboration with Naomi Kern

In collaboration with Naomi Kern

As part of our research process, we looked at some texts about domestic labor and gender, and how the combination of those two things lays itself out spacially. In the ‘80s, urban historian and architect Dolores Hayden wrote that “Home, sweet home” has never meant “Housework, sweet housework.” She wrote that home was a place of nuturing and support for men and children, which the mother figure of the hosue would provide. Women largely turned to each other when they themselves needed support, because they did not receive that care from their immediate families. Because of this, among other factors, women also tended to have stronger relationships with their neighbors. Domestic labor has therefore historically been woven into community connection and neighborly closeness.

The distribution of domestic labor inevitably creates hierarchy within the house. In our view, the homemaker will always be in service, in a way, to the other members of the household. However, in our project, we wanted to bring labor to the forefront of domestic socialization and community. We wanted to render the activity of the labor highly visible in the social spaces of the domicile, unlike the way domestic labor has often been pushed to the spatial and near-invisible ‘back-end’ of the house. Our core focus was thus on the union of labor and community.

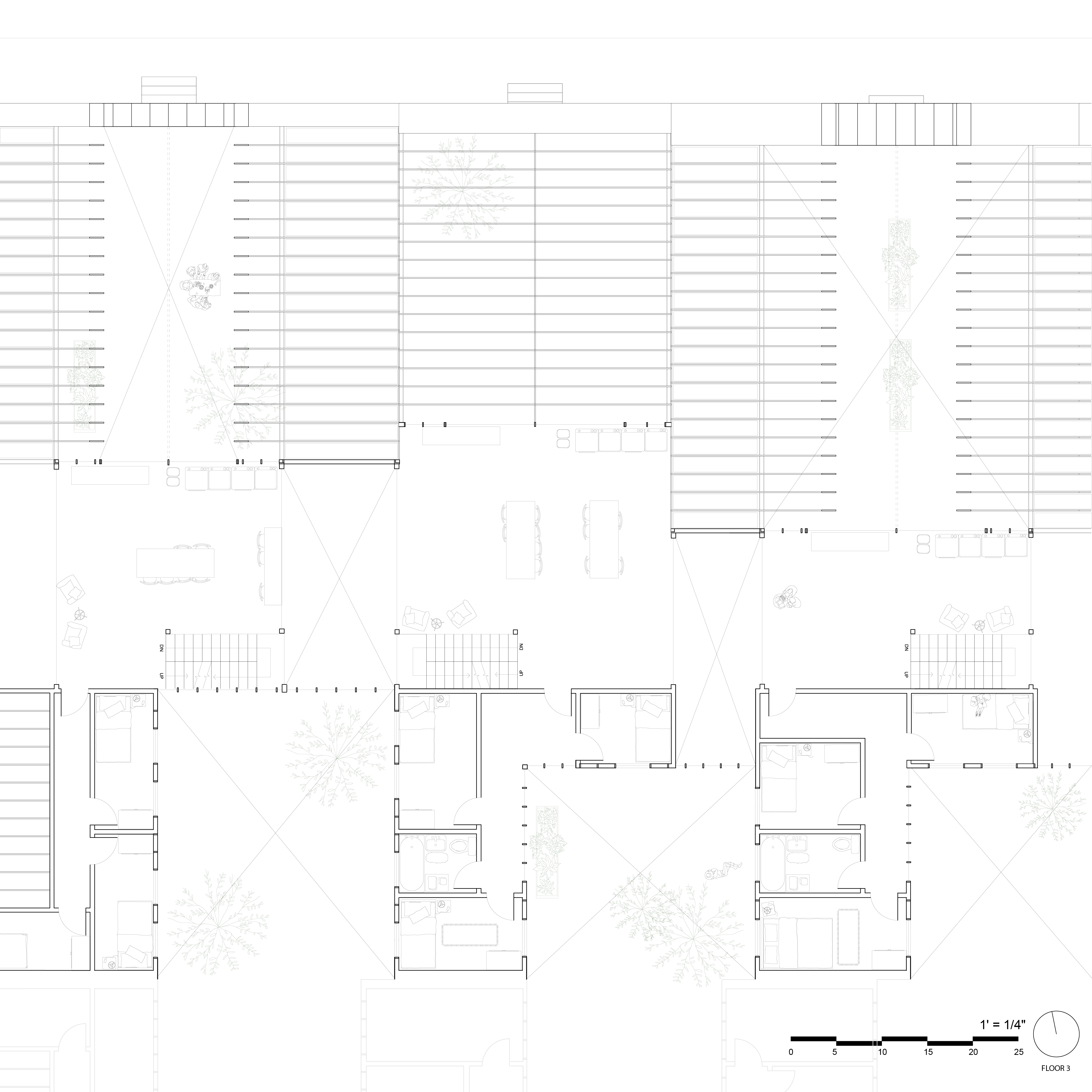

Throughout our process, we found that the building somewhat naturally divided itself into a ‘front’ and a ‘back’. We programmed the front, which included the social courtyard and the spaces packed around it, to include our hybrid labor and socialization spaces. Cooking and dining, laundry, and childcare and play are thus the primary activities that occur in the courtyard and its surrounding spaces, including on the upper floors. We designed this so that upon entering the courtyard, a person would be surrounded on nearly all sides by the various activities of domestic labor. The back, on the other hand, is where the private dwelling units are. These units include the minimal program of just bedrooms and bathrooms, which are organized around quieter, more private back courtyards. The size and spatial programming within the units is meant to encourage tenants to spend the bulk of their time at home in the social and labor spaces.

![]()

We carried out this emphasis on labor and community through the reappropriation of previous building elements. We preserved the method of entry of the front stoop, changing what was the direct entrance into an apartment into a somewhat choreographed path where a person would first have to walk through the social courtyard space. We stripped the previous house down to its wooden skeleton, and re-engaged the studs’ structural purpose by adopting them as mullions in the new exterior glass walls. In both courtyard types, the studs frame the outdoor space and give a palimpsest-style nod to the buildings that preceded our interventions. The new facade wall, which occupies what was previously the front setback dimension, relies on the previous window placements to reveal specific framed views of the domestic labor spaces and thus re-negotiate the relationship between the homemakers and the passing spectator. These views allow the laborers, in the eye of the passerby, to exist as the primary representation of the dwelling as a whole.